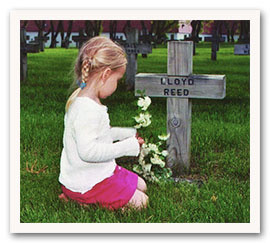

Children's Cemetery

In all, 198 State School children have been laid to rest in the Children's Cemetery. The Cemetery is open for public viewing, weather permitting. It has been restored by the Orphanage Museum and local friends. The first 47 children were buried with a tombstone. However, the practice then changed. The next 151 children who died were buried simply with their identification number etched on a slab of cement. Through a community effort, each grave now has a named marker.

In all, 198 State School children have been laid to rest in the Children's Cemetery. The Cemetery is open for public viewing, weather permitting. It has been restored by the Orphanage Museum and local friends. The first 47 children were buried with a tombstone. However, the practice then changed. The next 151 children who died were buried simply with their identification number etched on a slab of cement. Through a community effort, each grave now has a named marker.

A local newspaper reported on June 26, 1891: "A cemetery has been laid out on the State School farm which will be used for such of the Wards of the School who die there." Little could they imagine that this cemetery would become the final resting ground for 198 children.

The Orphanage Cemetery

by Volunteer Barry Adams (condensed from original version)

How terrible it is to die of inanition or marasmus, before age four, with no family at hand, and to be buried beneath a small stone with just a number. You will soon be forgotten. Most of us in the 21st Century are unfamiliar with "inanition” or “marasmus." Look at the standard medical definition: Inanition: emptiness; a state of advanced lack of adequate nutrition, food or water, or a physiological inability to utilize them; Starvation; a spiritual emptiness or lack of purpose or will to live; Marasmus: a form of severe protein-energy malnutrition characterized by energy deficiency. A child with marasmus looks emaciated. Do we see the definition as words on a page, or the experience of many of the youngsters who arrived at the State School? By the time they had arrived, some had already reached the point of no return.

The best medical care at the State Public School for Dependent and Neglected Children could not change the inevitable. Often, even with everything that Dr. Clifford McEnaney, Nurse Dorothea Putter, or the rest of the staff did, they could not change the course that child neglect had set in motion. The sadness of this reality hung like a cloud over the institution throughout its entire existence.

Of the 198 children buried in the cemetery, only 33 ever made it to age ten. Ninety-four were age three or under and 60 of those were under one. As we know, the state of medical knowledge is ever-changing, evolving, improving.

1905 Measles Epidemic

A vaccine for measles was licensed in the United States in 1963. Before that, measles was an expected part of life. In 1905 when the first case of measles was reported at the State School, a newspaper article showed little concern. But, if you walk along the first two rows of tombstones in the Children's Cemetery, you will find eight youngsters who died of this highly contagious disease...not one of whom had grown older than age three. Sisters Goldie, Lovie, and Jessie Jackson (pictured on right) arrived at the State School in Spring 1905. Lovie and Jessie died of measles three days apart in May. There were 50 cases of measles at the State School that year,

A case-by-case study of the burials offers an unlimited supply of human interest stories. Fourteen-year-old David Elmer Freeman is buried along the row of crosses closest to the west fence. Records simply say he died of a broken neck. But the boys who saw the football injury also saw the suffering on the ground and were present at the funeral. One hundred and ninety-eight burials are just the tip of 10,000 stories.